If you are interested in a seminar on any subject in Jujitsu or Restoration Therapy with the Professor, please contact us.

Popular subjects are:

- Fusegijutsu (self defense)

- Kappo/Sappo (to cure or kill)

- Seifukujutsu (healing arts)

- Keisatsu Gijutsu (police arts)

- Kiaijutsu (internal arts)

- KODENKAN JUJITSU OKUGI®

Email: Professor@Kodenkan.com

Phone: 408-260-0237

Professor Janovich has taught from the east coast to the west coast and overseas. Learn from one of the best in the world! He has taught Law Enforcement Officers throughout the country including FBI, Secret Service, State and local Police since 1973. Prof. Janovich has also taught at military bases teaching Army Special Forces, Navy Seals, etc since 1975.

Professor Janovich has taught from the east coast to the west coast and overseas. Learn from one of the best in the world! He has taught Law Enforcement Officers throughout the country including FBI, Secret Service, State and local Police since 1973. Prof. Janovich has also taught at military bases teaching Army Special Forces, Navy Seals, etc since 1975.

Seminar rates can vary, please call or E-mail for more information.

Prof’s Writings

THE PROTECTOR — Expanded Narrative Version

Copyright © 2025 Anthony P. Janovich, Jr. All Rights Reserved.

Silver Ridge, California, sat quiet between orchards and low hills, the kind of place where dust lifted slowly from the roads and the shadows of plum and peach trees stretched long in the evenings. In that town lived four generations of Vidaks, bound not just by blood but by something deeper—discipline, duty, and the quiet expectation that a man uses his strength for others.

Across a dusty driveway from the Vidak family home stood the house of Petar and Mary Vidak. Petar had come from Croatia in 1910 with the steel posture of a soldier and the gentleness of a man who understood hardship. He spoke mostly Croatian—Slav, as the family called it—and the rhythm of the language was as familiar to the Vidak grandchildren as the creak of the orchard windmill.

It was 1960 in Silver Ridge, the temperature was significantly higher on this June day. In fact, record temperatures were established in various California locations that year. So much for global warming nonsense, its all cyclical.

Marko Vidak Jr., still a boy then, spent most of his days after school and weekends in his grandparents’ yard and house. He watched his grandfather move with deliberate calm, and his father, Marko Sr., with a quiet authority that settled deep into the bones of anyone who spent time near him. The two men shaped the boy in ways schoolbooks never could.

He learned how to crack walnuts and almonds while sitting beneath a broad oak tree, helping his grandmother prepare them for sale to the bakeries in town. He helped his grandfather tend the fifty chickens on the farm—collecting eggs, planting crops, and cleaning the barn.

He remembered helping his grandfather load a fifty-gallon steel drum for burning trash, pausing now and then to eat fresh figs straight from the tree, or pomegranates, walnuts, and almonds—whatever happened to be in season.

Those early lessons—work first, family always—stayed with him long after the seasons changed.

CHILDHOOD – THE MAKING OF A PROTECTOR

Long before Marko Jr. came along, in the year 1936, his father—then eleven years old—stood behind the family home with a fistful of smooth river stones. Tin cans lined the fence behind the barn, sunlight glinting off their dented sides. He hurled the stones with speed and precision, each one ringing out a metallic crack as it struck home.

He didn’t know he was being watched.

His father, Petar, stood beneath the shade of a fig tree, arms crossed, the corners of his mustache turning up with pride.

“Marko, što radiš tamo?” he called.

(Marko, what are you doing over there?)

Startled, the boy turned.

“Bacam kamenje, Tata. Pokušavam pogoditi sve limenke.”

(Throwing rocks, Tata. Trying to hit all the cans.)

Petar stepped closer, examining the boy’s stance with a soldier’s eye.

“Imaš snažnu ruku, sine. Ali snaga sama nije dovoljna.”

(You have a strong arm, son. But strength alone is not enough.)

Then he switched to English, as he always did when a lesson mattered.

“You’ve got a gift, Marko. A strong arm, sharp eyes. You can hit anything you aim for.” He set a fallen can back on the fence. “But a protector knows when to use his strength… and when not to.”

The boy absorbed the words quietly, as if etching them into himself.

Later that day, Petar handed him a tennis ball and pointed to the barn wall.

“Nacrtaj metu… Draw a target. Throw the ball. Let it come back to you. More repetitions.”

Simple instructions, but profound in their purpose.

Years later, Marko Sr. would bring his own son, twelve-year-old Marko Jr., to the same barn wall.

“Your Grandpa taught me this,” he said, drawing a fresh circle in chalk.

The tennis ball slapped against the boards, bounced back, slapped again.

The rhythm echoed across generations.

A FATHER’S TEACHINGS

From the time Marko Jr. was five, his father taught him judo in the backyard, the scent of dust and freshly cut grass drifting on the breeze. The living room floor also served as a dojo. His father’s corrections were gentle but precise, his expectations high but steady.

“Sine, smiri se i osjeti protivnika.”

(Son, calm yourself and feel your opponent.)

Croatian mixed with English, discipline mixed with love, and the boy grew strong under both.

He excelled in judo—or, as his father called it, “combat judo,” another way of describing jujitsu. He also excelled in baseball, basketball, and football, the foundations of each taught by his father, along with their finer intricacies. Yet his father always reminded him that talent meant little without purpose—and strength without control was nothing at all.

He taught his son not only judo and sports but the meaning of integrity.

“Strength isn’t for yourself,” he’d say. “It’s for others. Always.”

These were not mere words—he lived them.

For his twelfth birthday, Marko Jr. was enrolled in the school of a world-renowned jujitsu master—a Japanese-German sensei from Hawaii whose presence filled the room like weather. Marko Jr.’s father, Marine Corps Sgt. Vidak, had met the master in Hawaii during the war.

He stood in the doorway during that first class, arms folded, watching proudly as another link in the Vidak chain began to take shape—quietly, deliberately.

THE WAR CALLS

By the early 1940s, Marko Sr. had become one of Silver Ridge’s brightest athletic prospects. He threw a fastball that cracked like splitting wood and a knuckleball that dipped with its own mind. When the New York Yankees offered him a contract, the town buzzed with pride.

But the world was at war.

With a sense of duty born of his father’s example, Marko turned down the uniform of the Yankees for the uniform of the United States Marine Corps. In 1944, he joined the Third Marine Division and sailed toward the Pacific.

War hardened him faster than childhood ever had. The jungles were dense, the heat oppressive, the nights alive with uncertainty. The boy who once threw stones at cans became a man who guided others through fire.

He rarely spoke of Guam or Iwo Jima, but the few stories he shared stayed imprinted on his son like scars. The following is one of those stories.

After Guam was secured, the Marines built a makeshift basketball court—an attempt at normalcy carved out of chaos. They played in the crushing tropical heat, sweat pouring freely, boots kicked off to the side, fatigue forgotten for a while as laughter echoed across the clearing. And of course, Marko Vidak owned the court—raining baskets, stealing the ball at will, and swatting shots with bone-rattling authority.

Until the crack of a Japanese sniper rifle cut the game short.

One second, a Marine was rising for a shot. The next, men were diving behind sandbags, retrieving rifles, returning fire. When the sniper was located, a small team moved out to eliminate the threat—Vidak in the lead, the best shot among them.

The game resumed afterward, like life insisting on its right to continue. That blend of danger and determination marked those days.

After Guam, he was sent toward Iwo Jima with the second wave of Marines. During the long ride over, Vidak found himself wondering what awaited them on that black speck in the Pacific.

What happened there is history now. But for Marines like Marko Vidak, it lived on as both vivid dream and recurring nightmare.

Chaos barely described Iwo Jima. Violent surf slammed the beaches as Marines struggled ashore under uncannily accurate enemy fire. The terrain itself fought them—soft black volcanic ash that swallowed boots and bogged down vehicles, making foxhole digging nearly impossible. Every yard forward was paid for under fire, in ferocious and devastating engagements.

Five days after the landings, the American flag was raised atop Mount Suribachi, a momentary surge of morale for the Marines below. But the island was far from secure. The fighting would rage on for thirty-six brutal days.

It was there, in the ash and fire of Iwo Jima, that Vidak learned chaos could be survived—but only by those who kept control when everything else was lost.

THE SHOTGUN THAT MISSED

When the war ended, Sergeant Marko Vidak found himself in Tientsin, China, helping oversee the repatriation of former enemy soldiers. Duty was never something he bragged about; he carried it the way his father had carried his own service—quietly, humbly.

He once told his son about a shift change at the main gate guardhouse. That night, he was the sergeant of the guard. The room was cramped, little more than a desk and a few chairs, rifles stacked neatly behind the counter.

A young Marine—fresh from boot camp and visibly jittery—was unloading his shotgun, a Remington “riot gun,” as procedure required.

Marko Sr. stepped backward, intending to sit in a chair behind him.

Just as he did, the shotgun discharged.

A thunderous blast tore through the wall inches above where his head had been. Buckshot embedded itself into the wooden planks like angry bees. Had he still been standing, he would have died instantly.

He told the story without theatrics, without invoking luck or fate.

“It wasn’t my time,” he said simply.

He never said how long he stood there afterward, staring at the hole in the wall, listening to the ringing in his ears—only that he finished his shift like any other day.

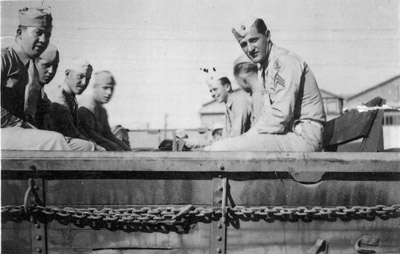

That moment stood in stark contrast to Sgt. Vidak’s usual Tientsin duty: escorting truck convoys transporting Japanese prisoners to ships bound for repatriation in Japan. His squad consisted of seven men plus himself, spread across three Jeeps, one Marine in each rear mount manning the .50-caliber machine gun.

He did occasionally speak about an escape attempt by a Japanese prisoner. One night, while he was serving as sergeant of the guard, a prisoner escaped his holding cell, severely wounding a Marine in the process and stealing his sidearm.

A search team was quickly formed, led by Vidak. About half an hour later, they spotted the prisoner running toward the compound wall. Vidak and his team gave chase. The prisoner climbed the wall and, upon reaching the top, turned and fired at the search team.

Vidak and the others returned fire. The prisoner fell from the wall, dead.

Vidak later told his son he could never understand why the man had tried to escape. He was scheduled to be sent home the very next day. War, he learned, did not always end when the fighting stopped.

Later that year, he told Marko Jr. that he was going to teach him how to use a knife—Marine Corps style. He brought out a Marine Corps Ka-Bar knife in its sheath and laid it carefully on the table between them. The room felt suddenly heavier. When Marko Sr. drew the blade free, the soft metallic whisper of steel filled the air. Marko Jr. noticed how the knife caught the light—shiny, silver, and flawless, like it had barely ever known rest.

“Do you remember the shotgun blast story?” Marko Sr. asked quietly.

Marko Jr. nodded.

Marko Sr. told him the knife had been a gift from the private who had nearly killed him by accident back at the main gate guardhouse in China. The private had nickel-plated it before giving it to him—an expression of regret, and, as Marko Sr. added with a faint, crooked smirk, probably a little ass-kissing too.

He carried it as his duty knife until he came home, where it was placed in a lockbox among other mementos and medals. He also kept his Marine Corps 1911 .45 auto pistol—one that would soon go back into service for the next chapter of Marko Sr.’s life.

Marko Jr. remembered his father pulling out a photograph of a ship called the USS Butner. He told him, “This is the ship I came home from China on.”

The voyage took about thirty days. The ship plowed through a couple of hard storms, the deck heaving under violent pitching, rolling, yawing, and sudden lurches that left many of the Marines seasick and miserable. His father, however, said none of it bothered him. He learned early that panic only made rough situations worse, whether at sea or on land.

Just like on the Pacific islands during the war, he never slept under a mosquito net, even though it was the norm. Laughing, he added, “The mosquitoes were afraid of me too.”

HOME AGAIN

When Sgt. Vidak returned home from the war, he traded his military rifle for a badge. The county sheriff’s office welcomed a man shaped by war yet grounded in humility. His sense of service became his compass through every call, every arrest, every family he protected. He also remained in the Marine Corps Reserves for the next ten years.

In fact, Marko Vidak Sr. was recruited by the Sheriff himself while studying police science in college after the war. It seemed the Sheriff kept files on every veteran in the program. When it came time to review Marko’s, the Sheriff flipped through the folder slowly, then stopped.

“Marine Corps sergeant. Pacific Campaign. Guam. Iwo Jima. China.”

He closed the file and studied Marko for a long moment. “You want to be a deputy sheriff?”

Marko met his gaze without flinching. “Sure,” he said. “Why not?”

In 1947, Marko Vidak was sworn in as a deputy sheriff. On a Saturday night during his first year on patrol, his photograph appeared in the local newspaper the following day. The image showed Deputy Vidak escorting a murder suspect out the front door of a popular local bar.

Deputy Vidak had been just two blocks away when the call came in—shots fired. He was the first to arrive on scene. He subdued the suspect and took him into custody.

The Sheriff arrived shortly afterward and informed him that reporters were already outside. He told Vidak to transport the prisoner to jail and have another deputy assist. As Vidak and the second deputy led the suspect out the front door, a newspaper photographer captured the moment.

The photo ran in the Sunday paper with the caption: END OF REUNION—a bullet hole through the suspect’s wrist, his shirt splattered with blood, as he was led away by deputy sheriffs after allegedly shooting his brother.

Deputy Vidak booked him into the county jail for murder—one of many arrests he would make over the next seventeen years, building a reputation the same way he lived his life: quietly, decisively, and without hesitation.

Deputy Vidak brought his upbringing, along with his Marine Corps training and values, into his work as a deputy sheriff. Whenever feasible, he warned suspects before any use of force. Control and restraint mattered to him just as much as strength.

For instance, around midnight on a Friday night, he responded to a call at another local bar. A man inside was challenging and fighting patrons. Deputy Vidak routinely made bar checks and made a point of knowing the managers, waitresses, and bartenders. They knew they could depend on him—to help, and to protect them.

That night, the bartender called the sheriff’s office to report a male customer who was fighting and provoking others. Deputy Vidak arrived on scene and entered the bar. The suspect stood at the bar screaming at the bartender. Nearby, a male patron lay on the floor clutching his stomach, reeling in pain.

Deputy Vidak ordered the suspect to place his hands on the bar and not move. He stepped in, patted him down for weapons, and informed him he was under arrest for assault and battery.

The suspect responded loudly, his voice loaded with profanity, claiming he was “just having some fun.” Then he sneered at Vidak and said, “If you didn’t have that badge and gun on, I’d show you a thing or two.”

Deputy Vidak met his eyes and said calmly, “Don’t say things you might regret.”

The suspect repeated the challenge, this time laced with the F-word.

Because of the trust he had built with the bartender, Deputy Vidak calmly removed his badge and gun belt and handed them across the bar.

“Okay,” he said evenly. “Show me a thing or two.”

The suspect threw a right-hand punch. Vidak blocked it, and almost with lightning speed delivered a palm strike to the suspect’s chin, followed by a leg sweep that put him flat on the floor. He rolled the man onto his stomach, secured him in handcuffs, then brought him to his feet and leaned him over the bar.

“Do not move,” Vidak said quietly, “or you’re on the floor again.”

The bartender handed back Vidak’s badge and gun belt and thanked him—another night restored to order, another reminder that Deputy Vidak never needed force unless someone insisted on learning why restraint mattered.

Over the years, Deputy Vidak answered countless calls. He stopped drunk drivers, mediated family and business disputes, and responded to shots-fired calls, robberies, kidnappings, disturbances, assaults, and burglaries, to name just a few.

He once told his son about a burglary call he answered at three o’clock on a Friday morning. At the time, Deputy Vidak was at the Sheriff’s Office substation in Silver Creek when a call came in for a burglary in progress at a jewelry store in the downtown area of a neighboring city, about two miles away.

Deputy Vidak jumped into his patrol car and drove at top speed. At that hour, the roads were empty. No lights. No siren. As he neared the rear of the store, he shut off his headlights, cut the engine, and coasted the final hundred feet in silence.

He exited the patrol car and approached the rear door of the jewelry store from the hinge side. When he was about three feet away, the door suddenly burst open. A man wearing dark clothing stepped out quickly, clutching a bag filled with jewelry.

Deputy Vidak later told his son that the sudden opening of the door had startled him—but training and instinct took over. In one fluid motion, he applied a control hold, took the suspect to the ground, and secured him in handcuffs.

From there, it was a short ride to jail—another reminder, he told his son, that preparation mattered more than speed, and control mattered more than force.

He told his son about another night on the job, sometime around 1950, when he responded to a call from a woman in the hills who reported a mountain lion in her backyard. When he arrived, the woman was frantic and visibly scared, leading him through the house to the rear sliding door that opened to a large, hilly backyard.

Deputy Vidak stepped outside, flashlight in hand, his Marine Corps .45 at the ready. The night was silent, but then, from the base of the hill about seventy-five feet away, he heard a low, guttural growl.

Moving toward the sound, his light flashed across the mountain lion. Its glowing eyes locked on him as it growled again, just fifteen feet in front of him. Without hesitation, Vidak used the same commanding tone he had learned in the Marines and shouted, “Get the hell out of here!” His .45 was aimed directly at the lion’s head, his voice echoing off the hills.

He said the mountain lion was huge—about 150 pounds—and for a moment, he and the animal simply stared at each other. Vidak was ready to fire, his .45 loaded with 230-grain bullets. But the lion growled one last time and then, as if deciding this was not its fight, turned and bounded up the hill.

The woman thanked him, wide-eyed. “I’ve never seen anything like that in my life.”

Maybe it was Vidak’s six-foot-two, 220-pound frame, or the voice that could intimidate even King Kong, she said, that made the mountain lion run.

Marko Jr. sure knew that stance and voice of authority firsthand—and he understood exactly why the cat ran for the hills. Marko Jr. could hear the same authority in his father’s voice even now, and he recognized it later in his own commands, understanding why some people—or animals—knew not to test the Vidak name.

Marko asked his father how the rest of the night went.

Marko Sr. smiled faintly. “Funny you should ask,” he said. “I got another call—closing time—at the same bar where I arrested that murderer three years earlier.”

This time it was a disturbance: a male subject refusing to leave, throwing beer bottles against the walls.

Deputy Vidak arrived and confronted the man near the bar. Empty beer bottles sat along the edge, waiting to be tossed out. The subject stood about six feet away, leaning back against the bar. Vidak positioned himself at an angle and told the man it was time to leave. When the subject refused, Vidak warned him he would be arrested if he didn’t comply.

Instead, the man grabbed an empty beer bottle, smashed it against the edge of the bar, and held the jagged glass out in front of him.

In a calm, steady voice, Vidak said, “You have three seconds to drop the bottle—or I’m going to break your arm.”

Before the count reached two, Deputy Vidak stepped in. He applied a combat judo armbar with decisive precision. There was a sharp snap as the arm broke. Vidak cuffed the man, and the next stop was the county jail.

Everyone in the bar stood frozen, hardly believing what they had just witnessed. The deputy could have shot the man—but instead, he chose to disarm him. It would have been considered a legitimate police shooting; the threat of great bodily harm or death had been real and immediate.

“That’s what control looks like,” he told his son later. “You don’t rush it—and you don’t hesitate.”

1950 was also the year Marko Vidak married Emma Dubois. Marko met her during a dinner break on one of his shifts, while eating at a popular café not far from the Vidak farm in Silver Ridge. Emma was a waitress there.

They married and raised three children—two daughters and a son, Marko Jr. That son would sometimes ride beside his father on patrol, watching and learning what it meant to be a man who could stand his ground without losing his kindness.

From the passenger seat of the patrol car, he also witnessed moments when a routine contact with a suspect turned physical. The lesson was unmistakable. One moment the fight was on; the next, his father was calmly securing the suspect in handcuffs. The criminal never stood a chance.

From that passenger seat, Marko Jr. learned that strength, when paired with discipline, ended fights quickly—and spared everyone unnecessary harm.

THE SON BECOMES THE STUDENT AND THE TEACHER

Marko Jr. grew into a man molded by his father, grandfather, and jujitsu master—Sensei, as he called him—physically disciplined, mentally calm, and spiritually grounded in purpose. He followed in his father’s footsteps, entering law enforcement and teaching military and police combatives.

Marko Jr. believed the most important work in policing was done as a patrol officer, working the streets. When something happened in the city, it was the first responders who arrived first—to assess the situation, take control, and protect those involved.

He trained recruits to keep their wits under pressure, to read a room, and to stand between danger and the innocent. He carried his father’s lessons like tools on a belt—always available, always needed.

There were many stories Marko Sr. told his son over the years, some of them more fitting to share once Marko Jr. began his own career in law enforcement. Often, Marko Jr. would describe an incident from his patrol shift, and his father would respond with a story from decades earlier—lessons resurfacing when the time was right.

One such story involved a domestic violence call, as it would be known today. In Marko Sr.’s day, it was bluntly called a “wife-beater” call. He arrived on scene, arrested the husband, and transported him to the county jail.

As he was removing the prisoner from the patrol car at the old jail, the man suddenly broke free and ran. Vidak drew his .45 and took aim—but then stopped. As he later put it, “I wasn’t going to shoot a wife beater.” He holstered his weapon, radioed in the escape, and an all-units bulletin went out over the air.

A short time later, two local PD officers returned with the prisoner in custody. They had caught him running through the park across from the jail. As they walked him back inside, one of them asked Vidak, “Lose something?”

Vidak smiled and said, “I owe you guys one.”

It was one more reminder, he told his son later, that wearing a badge didn’t mean surrendering judgment—only learning when to use it.

When his own son, Nick, was born, Marko Jr. recognized the old Vidak fire in the boy’s eyes even before Nick could walk. The child grew into a young man who listened closely to stories of Grandpa Marko and Great-Grandpa Petar. Croatian phrases found their way into the boy’s vocabulary, just as they had with each generation before.

One day, Nick told his father he planned to join the U.S. Marine Corps.

There was pride in Marko Jr.’s chest, but also the tug of something deeper—fear mixed with recognition. He knew what awaited a young Marine. He also knew he could not deny his son the path that belonged to him.

Nick became a Field MP, carrying forward the Vidak legacy of protectors. Three generations now stood in uniform—four, if one counted Petar, who had served decades earlier in the Austro-Hungarian Army.

When Nick shipped out, father and son exchanged an embrace that held not just two men, but the weight of all those who came before. Then came a farewell embrace from his proud grandfather, former Marine Corps Sgt. Marko Vidak Sr.

THE LEGACY REMAINS

In the house that once belonged to his father, Marko Jr. still felt their presence. Petar’s discipline. His father’s courage. His own years as an officer. His son’s determination.

The home was more than walls—it was a living echo of the men who had shaped him.

Sometimes he would walk through the quiet rooms and imagine his father at the kitchen table, polishing his badge after a long shift. Or Petar in the yard, straightening a fence post with the same focus he once gave to military drills. Or young Nick in the doorway, asking when they could practice judo again.

The lineage was unbroken, bound by love, discipline, sacrifice.

Marko Jr. often hoped his father could see the man he had become.

And he believed, in the still moments—when the sunlight came through the window just right, or when the orchard breeze rustled the leaves outside—that perhaps his father did see.

Perhaps all of them did.

EPILOGUE

In the quiet of late evenings, Marko Jr. sometimes pictured a familiar scene: Petar standing beneath the fig tree, arms crossed, watching. Behind him, Marko Sr. with his strong shoulders and steady gaze. And beside them, young Nick in Marine uniform, the next protector in line.

Four generations.

Four men bound by an unspoken oath.

Strength is a gift—but only if used for others.

The orchards of Silver Ridge still whisper with memory, and Marko Jr., walking the land his father left him, carries their lessons forward.

And every step he takes, he hopes—

that he has made them proud.

The Protector — A Short Story Inspired by the Life of Anthony P. Janovich, My Dad

Copyright © 2025 Anthony P. Janovich, Jr. All Rights Reserved.

He was born in the shadow of the California hills, in a small town called Mountain View — back when the streets were dirt, the summers smelled of hay and orange blossoms, and boys dreamed with a mitt in one hand and the world in the other.

From the time he could walk, he could throw. Baseball came to him like breathing — natural, effortless. In high school, he was the kind of athlete folks didn’t forget. He could sink a basket from the far line, tackle like thunder, but when he stood on the pitcher’s mound, the world went still. The New York Yankees saw it too — they handed him a contract before the ink had dried on his diploma. A farm team, a fastball like fire, a knuckleball that danced like a ghost. His future seemed carved in the red clay of the diamond.

But the world was at war.

And for him, there was no question which field needed him most.

He hung up his glove and put on the uniform of the United States Marine Corps.

He went to the Pacific — Guam, Iwo Jima — places where courage was measured not in words, but in moments. He rose to sergeant, led men through chaos, and when the guns fell silent, he found himself in China, helping to send men home who had once been the enemy. Duty wasn’t something he spoke about — it was just who he was.

When the war ended, he came home, traded his rifle for a badge, and joined the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office. His sense of right and wrong was as steady as his aim. He became a protector again — this time of streets and neighbors. His picture once made the front page, taking a murderer into custody. But that wasn’t pride — just another day’s work in the long line of service he believed in.

He married a good woman in 1950, raised three children — two daughters and a son. That son would ride beside him sometimes on patrol, watching, learning what it meant to be a man who stood his ground without losing his kindness.

He was tough — a Marine sergeant through and through — but he laughed easily, too.

He taught his boy baseball and judo, how to stand tall, how to defend the weak. When his son turned twelve, he sent him to train under one of the world’s greatest masters — as if he already knew the path that boy would one day walk.

Years later, that son would wear a badge himself. He’d teach soldiers and officers how to fight, how to survive — and how to serve. He’d raise his own son, a U.S. Marine, carrying the same torch lit so many years ago by a young man from Mountain View who gave up a baseball dream for something greater.

Ninety-seven years is a long road, but he walked every mile of it with purpose.

Even now, in the house he built and left behind, his spirit lingers — in the creak of the floors, the smell of the glove he once oiled, the feel of honor passed from father to son, and then to grandson.

Because some men don’t just live a life — they build a legacy.

And for those lucky enough to be his family, that legacy has a name:

Protector.

Song

“My Dad, The Protector”

Written by Anthony P. Janovich

Copyright © 2025 Anthony P. Janovich. All Rights Reserved

A heartfelt country storytelling ballad titled “My Dad, The Protector.”

Sung from the perspective of a son reflecting on his father’s life — a proud U.S. Marine from the Third Marine Division who gave up a baseball dream to serve his country, became a sheriff’s deputy, and taught his son about service, honor, and protecting the innocent.

The tone is nostalgic, proud, and deeply emotional.

Style inspired by George Strait, Alan Jackson, and Vince Gill.

Medium tempo, rich baritone male vocal, classic country instrumentation: acoustic guitar, steel guitar, fiddle, bass, and standard country drum kit.

Lyrics — “My Dad, The Protector”

Copyright © 2025 Anthony P. Janovich. All Rights Reserved.

[Verse 1]

He was born in Silver Ridge, a small-town son,

Big hands, strong heart, second to none.

Could’ve pitched for the Yankees, the stories all say,

But duty called louder, and he walked away.

[Chorus]

My Dad, the protector, stood tall and proud,

A Marine through the fire, he never backed down.

From the islands of battle to the streets back home,

He taught me to serve, to stand on my own.

He said, “Son, when it’s hard, and the world turns cold,

You protect the weak — that’s worth more than gold.”

[Verse 2]

Came home from the war, traded boots for a star,

A badge on his chest, he raised the bar.

Taught me judo at five, how to fight and be kind,

How to lead with your heart and your honor aligned.

[Chorus]

My Dad, the protector, with a steady hand,

He showed me how to be a man.

He said, “There’s right and wrong, no in-between,

Keep your soul clean, live your dream.”

[Bridge]

Now I wear that badge, just like he did,

Teaching what he taught me when I was a kid.

And my own boy’s a Marine, proud and strong —

Three generations, the legacy lives on.

[Final Chorus]

My Dad, the protector, his spirit’s still near,

I feel him in the wind, I see him clear.

In the house he built, in the life he made,

In the lessons and love that will never fade.

Yeah, my Dad, the protector… lives on in me today.

Tags (optional, for better results):

Country, Ballad, George Strait style, Heartfelt, Father and Son, Marine, Emotional, Legacy, Storytelling